I really enjoyed reading Jose Lopez’s blog post, and wanted to comment on how Sake Dean Mahomet doesn’t similarly do the same with the individuals, or those outside of power; thus complicating the story further. In class, we had discussed a section where Mahomet describes the lives of Muslims, and even determined from this his own position as a Bengali Muslim working for the East India Company. Within his travel account, or travelogue, Mahomet instead imitates Orientalist literary passages to subvert British colonial violence when focusing on the peaceful, seemingly mild moments within his own travels: opulent imagery, thorough description, and implicit light-heartedness in many passages choose to go against the violent and antagonistic Muslim/Hindu relationships purported by the British.

A common trend within “Oriental” works, according to Said, involves one’s submission to being an “Oriental figure” unwillingly, as one could be “place[d] by an average nineteenth-century European, but also because it could be–that is, submitted to being–made Oriental,” determining that a lack of consent was found in, for instance, “Flaubert’s encounter within an Egyptian courtesan” establishing this trope (Said 5).

Said (5)

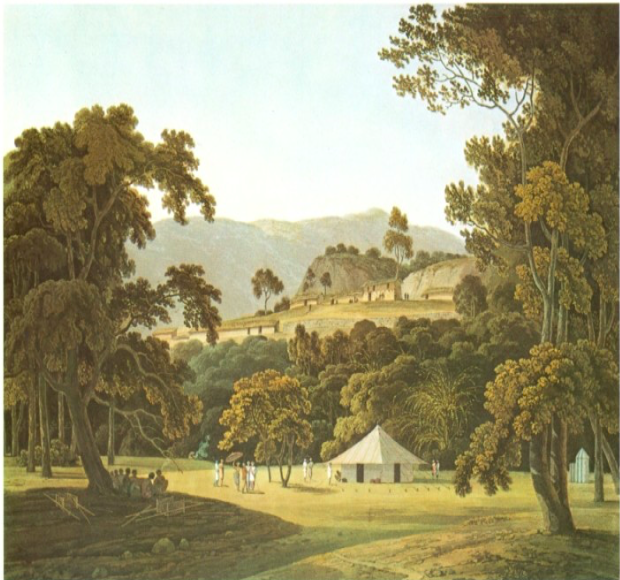

Mahomet “takes breaks” in between discussing wars and murders throughout his travelogues by humanizing the people that are involved within the text, and adds context to the women within “Orientalist” travelogues. The gender imbalance seems inherent within a “Dean Mahomet” epistolary novel rather than a “dancing girl” (70) epistolary, and similar to British “Orientalist” travelogues, but Mahomet speaks for these women, and does so from an more ‘insider’s perspective’ (whatever that indicates for you is probably intentional — how exactly does he know about these dancing girls, their matrons, and their “occupying the handsomest houses in the towns or cities” (70-71)) rather than as a lusting British traveler. When he implies his own experiences with watching these women through a “public” and “private” (71) setting, stating that “all these love-scenes, they perform, in gestures, air, and steps, with a well-adapted expression,” he does this through an objective, traveler’s perspective rather than utilizing a first person perspective and forcing a singular European male gaze upon the women. This is furthered with the lack of sexualized depiction, and Mahomet’s focusing on the world outside of the dancing women: the content of his work slides around their own actions, “these creatures” (his words not mine, 71) are “recruited out of the people of all casts and denominations, though not without a peculiar attention to beauty or agreeableness; yet even the knowledge of their being so common, is with many totally forgotten in the ravishing display of their national and acquired charms” (71). He continues objectifying them in the manner the British do, in many ways, describing them as “creatures” and focusing on their “bodies,” but adds details and descriptions that reinforce British opulence and British views of the sublime. This passage from Pramod K. Nayar’s work describes British desires for opulence (if y’all really want to read it):

Within this, he critiques the mannerisms and dress of these women in a comparison to European prostitutes, through using the aforementioned “rhetoric of inflation” in describing their mannerisms in a form of opulent diction that mimics British intrigue and sexualization of Indian women. Mahomet places these women on a pedestal and asserting their superiority to “Western women” by describing the “gross impudence which characterises the European prostitutes; [the Indian women’s *(unsure if Muslim and/or Hindu)] style of seduction being all softness and gentleness…there are some of theme, even amidst their vices and depravity whose minds are finely impressed with generous sentiments” (72). Not only this, but he does in a way critique the women and men who engage in these activities as a whole: by indicating these women as engaging in “vices and depravity” yet still having minds “finely impressed with generous sentiments,” he doesn’t exactly discuss the men who involve themselves in such business as well, and doesn’t offer the men, British or Indian, a meaning behind their own engagement with “vices and depravity” (72). Although I would love to analyze the main passage that ends his epistolary within Letter XV further, he gives women “of the country” (72) a backhanded compliment in many ways, as he ends with the moralistic statement, “even the human heart plunged in crimes and immorality, may sometimes be roused from its torpor by the voice of humanity” (73) and criticizing European prostitutes (72) (so how does he know about all of this in the first place :)?).

Mahomet’s mentioning of Omrahs in many ways justifies British colonialism and imperialism, but it does call into question how hegemonic this perspective reigns throughout the work with Mahomet’s notable tangents; in many ways, he subverts a travelogue by utilizing tropes within the travelogue, and when doing so, makes a light of these topics and normalizes them. In this, I’m on the fence based on Lopez’s argument and my own findings due to how conflicting Mahomet is as a writer.

Samantha Shapiro